Bisexuality

Abstract

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender are the beginning myriads of defining sexuality. People and concepts are consistently evolving – so are these labels important factors for developing identity? Could these categories be a means of isolation and discrimination within the LGBTQ+ community? This visual rhetorical analysis explores normalities, conformities and controversies of bisexuality.

Introduction

Two females are in close proximity of each other. Cool tones of blue light reveal the freckles of one nose touching another while warm hues of red luminate lips pressed together. The woman in the left of the photo has her eyes closed. Loose, brown hair covers part of the right woman’s face with the exception of her nose, lips and chin which features a small mole on her fair skinned complexion.

This photo “The Kiss” was found on an LGBTQ+ Tumblr page and is the first visual representation of my chosen community. The intimacy of this imagery may create some discomfort for external audiences who are likely to assume it captures two lesbians sharing an affectionate moment. However, my internal LGBTQ+ audience is more likely to identify precise symbolism through subtle artistic choices. They collect unspoken context in the work that explicitly helps them interpret the visual language. One example is the color-scheme in the photograph which mirrors the bisexual pride flag. Knowing this information allows them to appropriately determine the sexual orientation.

Defining Bisexuality

A graphic of a pink, purple and blue diagonally striped name tag reads ‘Hello, I’m bisexual.’ The name tag lies on a solid black, square background. Today bisexuality is defined as the “romantic attraction, sexual attraction and/or sexual behavior toward both males and females” Merriam-Webster (2019).

Alfred Kinsey founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University in 1947. His work quickly gained momentum as he studied the sexual behaviors of 11,240 males and females through in-person interviews. Kinsey found “37% of males and 13% of females had at least some overt homosexual experience to orgasm” Castleman (2016). This research sparked further curiosity on classifying sexual orientations and became pivotal to the field of sexology in the 19th century.

Ideology & Identity

Two people wear white t-shirts and stand facing one another. The person on the left has their arm extended and hand placed on the right person’s chest. A vivid, red glow borders the palm and fingertips of the hand and contrasts the picture’s overall dark shadows. The setting is left unclear.

“To read an image like an argument, it is important to think about its purpose. Critical analysis is not to guess intentions, but to create meaning supported by the evidence presented” Melzer (2011). Without knowing the sex, gender or orientation of the subjects in this photo we are still able to discern a sense of romance and strong, gravitational pull. Newton says we attract and conform to the particles around us and in relationships, that’s our partner. Witnessing bisexuality from an objective viewpoint helps us focus on the orientation’s intrinsic needs of intimacy, passion, communication, commitment, affection, trust, self-disclosure and an inherit sense of belonging.

Stereotypes & Stigmas

A subject stands center frame wearing a white t-shirt, dark pants and matching, black bracelets. Pink, purple and blue pigments are on the skin smeared by multiple hands touching and tugging at them. Their eyes are closed, mouth clenched and arms held up partially covering the face and body.

Bisexuals don’t exist. It’s just a phase. Are you even bisexual if your partner is the opposite gender? Bisexuals are straight women playing lesbian. People claim bi to justify wreck-less relationships. Bisexual men are gays who just haven’t come all the way out of the closet. So 1/2 gay, 1/2 straight?

“Concerns in coming-out are self-doubts and uncertainty towards people’s response to their decision to come-out primarily due to the lack of understanding about their sexual orientation” Masanda (2017). Approximately 40% of bisexual people have considered or attempted suicide according to the Bisexual Health Awareness Center. These numbers are believed to be higher than those of gay men and lesbian women due to the prevalence of biphobia in LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ spaces alike Human Rights Campaign (2019). Rejection can develop apprehension into a perception of diminished social standing, discrimination, shamefulness, low self-worth, suppression, isolation and suicidal ideation. Only 28% of bisexual people report being ‘out’ to close family and friends.

Personal Experiences

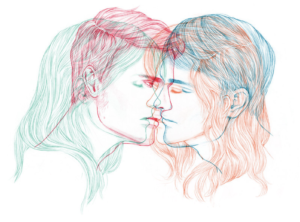

Thin outlines of different people depicting both sexes overlay each other using various colors. The four illustrations are facing each other with heads tilted, eyes closed and mouths nearly touching.

Born and raised in the narrative of an extremely religious, rural hometown – open-mindedness to LGBTQ+ sexualities wasn’t accepted or welcomed. My first same-sex relationship was shortly after joining the military. I was excited to express a forbidden part of my identity yet scared to be vulnerable, naked both physically and emotionally. She was patient and kind, but my conscious was not. As time passed, I could no longer share my dinner dates and weekend plans with family or grant my girlfriend the clarity and depth in the relationship she deserved. It’s a pretty crappy feeling to live knowing whichever path you take will certainly be shadowed in disparity. I thought coming-out would be a relief, weight off of my shoulders and finally accountability for the person I wanted to be moving forward. It wasn’t any of those things, instead, it taught me it’s okay to hurt…

Pain is your mother’s first response to you coming-out, asking if your father ever inappropriately touched you as a child that made you what you’ve become. Pain is boarding a plane to a different country, not knowing if you’ll have family or a girlfriend left anymore when you return. And pain is the unrealistic expectation that the LGBTQ+ community is always going to have people available to help during these seasons of brutal transition, only to discover support can be scarcely fickle.

Conclusion

Pain taught me sometimes I have to let go, even if it feels good in the moment. Pain taught me not everything I lose is a loss after all. And pain is still teaching me how to appreciate the peaks and valleys that lead to contentment when I find grounding in the nutrients of self-care and love. Coming-out is not an act with three scenes and a curtain closing on happily ever after. Being bisexual is a constant evolution from the person I was on a date with my first girlfriend six years ago, to the person I aspire to be – an eighty-five-year-old, tattooed cat lady – at peace with herself, sharing the magic of life and a glass of wine with her partner in the hidden mountains of somewhere.

Posted on International Bisexual Visibility Day • 23 September 2019 • by Cambria Lynn Ferguson

Citations

• Castleman, M. (2016, March 15). The Continuing Controversy Over Bisexuality. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/all-about-sex/201603/the-continuing-controversy-over-bisexualityHuman Rights Campaign. (n.d.).

• Human Rights Campaign. (2019). Bisexual Health Awareness Month.

Retrieved from https://www.hrc.org/blog/bisexual-health-awareness-month-mental-health-in-the-bisexual-community

• Masanda, A.B. & Armentia, G.A.P. (2017). Coming-Out and Romantic Relationship among Female Bisexual Adolescents. Progress in Asian Social Psychology, 11, 79 – 87

• Melzer, D., & Coxwell-Teague, D. (2011). Everything’s a Text: Readings for Composition.

New York: Pearson Longman

• Merriam-Webster. (2019). Bisexual.

Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bisexual